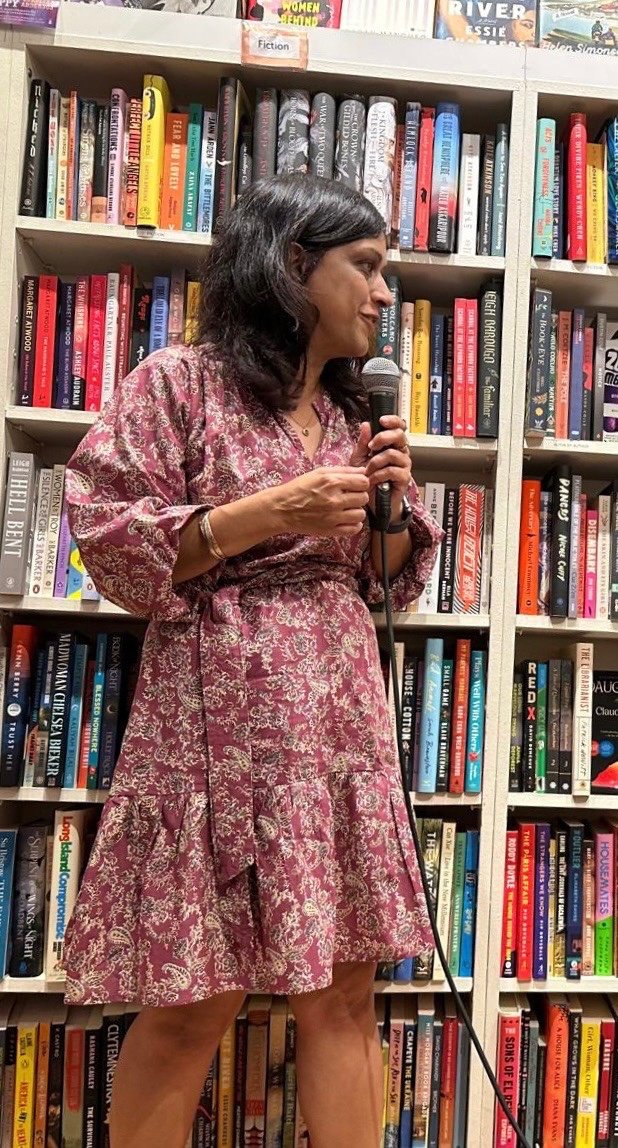

Decolonising the Couch with Dr. Pavna Sodhi

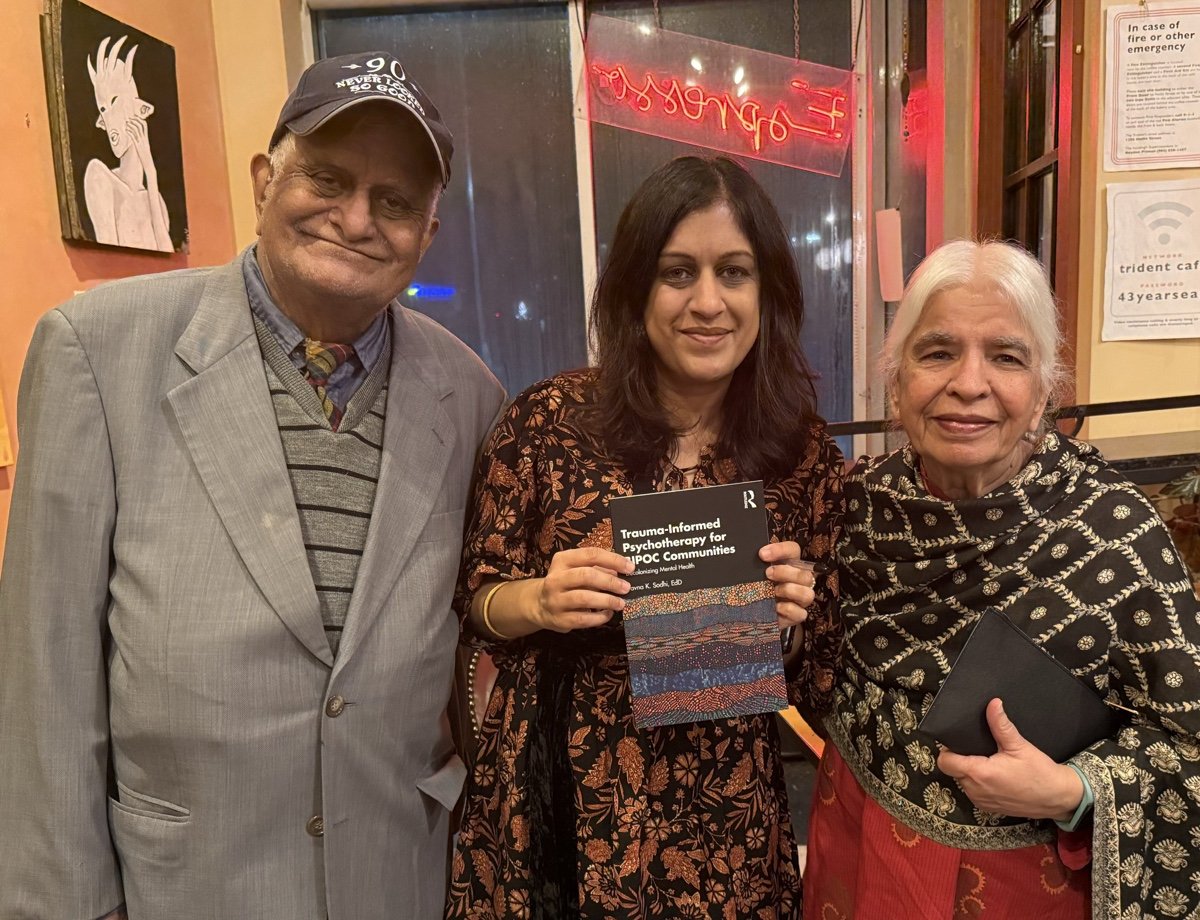

Introduction: I’m a registered psychotherapist, author, speaker, and adjunct professor residing in Ottawa, Ontario. I was born in Halifax, Nova Scotia and socialized by two voluntary immigrants. For over 20 years, I have provided psychotherapeutic services to BIPOC, immigrant, and 2SLGBTQIA+ communities, which resulted in the authorship of my book regarding these demographics. I credit my multifaceted upbringing, travels, and lived experience for gravitating towards this psychoeducational field. From here, my interest in multicultural, immigrant, and culturally responsive work started in graduate school. My research focused primarily on immigrant populations and identity formation and the notable influences towards one’s bicultural identity formation.

My research is anchored in social justice, critical race, and feminist principles and theories. For the last 25 years, I have conducted research focusing on enhancing both awareness and respect towards multicultural populations, and I have built upon my initial curiosity surrounding various models of identity formation. Since graduate school, I have learned that there is no shortage of multicultural research questions; there is, however, still a scarcity of literature about these much-needed topics, including content about culturally responsive trauma-informed practices.

Lastly, in accordance with self-reflexivity, I recognize my privilege and power in terms of my intersectionality and worldviews. I identify as a second-generation South Asian Punjabi-Sikh, neurodivergent, able-bodied, and heterosexual cisgender female. Other aspects of my intersectionality that have enhanced my privilege include being a mother, a child of educated voluntary immigrants, and having credentials and financial resources to be gainfully educated within a Canadian school system.

1. How do you handle racism or sexism from clients, particularly when it comes to both macro and microaggressions? Where do you draw the line between protecting yourself, such as by terminating a client, and using the moment as an opportunity to educate them?

This has been a work in progress! Earlier in my career, I would often react negatively to clients’ microaggressions and racial gaslighting; however, over the last decade, I have chosen to reframe these situations and instead create teachable moments for clients to become more culturally curious rather than culturally ignorant.

I detail this process in my book, Trauma-Informed Psychotherapy for BIPOC Communities. As a BIPOC psychotherapist, I would like to share a personal narrative, titled The Cultural Elephant in the Room, that I wrote after experiencing a common microaggression from a client:

As we collectively raise awareness around anti-racist causes, it is important to implement relevant approaches in our clinical practices. The cultural elephant in the room can consist of, but is not exclusive to, microaggressions, cultural ignorance, shadeism, internalized colourism, generalized racial stereotypes, and covert racism that occurs within the therapeutic space (or any space, for that matter). Clients are generally at the receiving end of culturally inappropriate comments. However, as a psychotherapist, I have experienced uneasiness and discomfort while navigating this familiar territory.

During the summer of 2020, a client asked me, “Where are you from?” It has been over a decade since I have been asked this question, so I decided to frame my response as a teachable moment for the client. I said, “I was born in Canada.” She looked at me with confusion, so I added, “My parents are originally from India.” I then asked her if she was familiar with the culture, and she said no. I decided to share what I have learned about the culture (e.g., Eastern worldviews such as self-compassion, loving kindness) and how this informs my practice. These details resonated with her and offered a piece of cultural knowledge that she was not aware of prior to working with me. I believe discussing her inquiry strengthened the therapeutic alliance.

The same method (i.e., reflecting, exploring one’s worldviews, and linking my response to my therapeutic approach) can be applied if a client makes a racist remark about a cultural group or labels a cultural group in a derogatory manner. The unlearning and relearning dialogue can begin by asking the client about their understanding of the culture, exploring the history of the cultural group, and concluding by reminding the client of this population’s contribution to society.

As therapists shift towards becoming more antiracist practitioners, every teachable moment is necessary to eradicate systemic and structural racism and educate others on the importance of being empathic and respectful to humankind.

2. How do we stay in this profession, knowing the historic harm this field has caused?

My purpose in continuing in this professional domain is to dismantle systemic harm and oppression towards BIPOC practitioners and diverse marginalized communities. In doing so, I have created decolonial frameworks that debunk the notion that therapy is a one-size-fits-all modality and stems exclusively from mainstream, Western, Eurocentric, and individualist ideologies. To decolonize one’s thinking, we must extricate ourselves from the colonial ways of being and recognize that mental health is highly influenced by one’s trauma narrative and encounters with systemic oppression.

Decolonizing mental health allows a practitioner to draw from antiracist, trauma-informed, anti-oppressive, culturally responsive worldviews. It includes the following considerations:

Look beyond symptomology and explore the root cause of potential mental health conditions; avoid diagnostic labelling/pathologizing.

Engage in cultural humility; become culturally curious, self-reflective, and learn from our clients, who are the experts of their narratives.

Lean into one’s intersectionality and provide therapy grounded in Eastern ideologies and collective healing.

Recognize the significance of staying current in our language and messaging while working with intersectional clients. Establish trust and safety with clients.

Normalize therapy by walking alongside, meeting the client where they are at, exploring unwelcomed systems, and posing supportive and reflective questions.

3. In what ways does sharing a cultural or racial identity with your clients influence the therapeutic relationship and outcomes?

This is part and parcel of disclosing one’s intersectionality, which is a practice I share during the complimentary consultation with prospective clients. It allows clients to determine therapeutic fit based on the lived experiences that I bring to the therapeutic space.

Additionally, it’s an offering for clients to acknowledge their intersectionality, mutual commonalities, shared language and experiences that might be represented in the therapeutic dialogue. I have found disclosing my intersectionality beneficial in establishing foundational safety and trust with the client during the initial stages of treatment planning, as well as an opportunity to build upon the therapeutic rapport during various parts of the therapeutic process.

4. How do you assert yourself as a racialized woman in primarily white and often male-dominated environments, especially during strategic planning?

This continues to be the story of my life – whether I was able to name it in the past or not. This started during my graduate studies at the University of Ottawa. I was the only South Asian student in the program; mind you, this was in the late 1990s and pursuing an arts-based program was very uncommon within my community and cultural peer group. There was clearly a lack of representation of racialized and intersectional folks within the program. I had a bit of reprieve during my doctoral studies at the OISE/University of Toronto, where I felt more of a sense of belonging with a culturally diverse student representation. There was instant camaraderie, as well. Once I returned to Ottawa for personal reasons, I tried for several years to secure employment as a tenure-track professor at local educational institutions, as this was the main reason for pursuing an EdD. Not only was I confronted with racial and sexist barriers, but I was also expected to teach in French. At times, I felt I was trauma-responding over the years as I tried to assert not only my competencies but also engaged in some people pleasing. Therefore, to have some classroom presence and connect with students, I chose to apply for contract teaching positions, which have been rewarding, but also a reminder of the fact that I do not meet the standards that these schools are achieving. Yet, as a result of not being hired, I have learned to pivot and instead started a private practice and remain current in my research and publications, which has been very fulfilling in and of itself.

5. What unique challenges do racialized students face in this field?

One of the challenges or barriers that racialized students experience in academia is the lack of representation of intersectional and decolonial educators. Subsequently, these students are often discouraged from applying to programs where faculty are primarily occupied by white professors with limited experience, knowledge, and/or interest in supporting BIPOC or social justice calls to action.

As noted in my book, in my quest to decolonize academia, I make suggestions to curate a more inclusive classroom environment. These offerings are:

Share intersectionality: Develop an authentic presence

Celebrate learners’ cultural diversity

Build trusting relationships with students

Create a safe and equitable academic space

Curate a community of lifelong learners.

6. You’ve been in this field for over 25 years, which is a huge accomplishment. How do you cope with these challenges? Do you have any strategies or tricks you would be willing to share?

Thank you! Yes, over the last 25 years, I have acquired several rewarding personal and professional experiences. In terms of managing systemic challenges, I have immersed myself in decolonizing all of my professional spaces: therapeutic, research, academic, and supervisory. I believe every effort counts, and we must all work together to create long-term, sustainable change. Again, I lean into teachable moments when needed and respond versus react to any form of racism.

7. What topics should be prioritized in counselling programs to better prepare future therapists?

I believe it is essential to infuse and talk about culturally diverse topics within all graduate-level courses. This will better prepare practitioners to effectively work with intersectional clients. I have had the opportunity to teach the Multicultural Counselling course at the University of Ottawa. My syllabus provided the following learning intentions:

Acknowledge how both the counsellor’s and the client’s intersectionality (i.e., social identities comprised of culture, ethnicity, race, religion/faith, spirituality, language, gender, gender identity, social class, sexual orientation, ability, education, and age) influence the counselling alliance and delivery of culturally responsive counselling services.

Explore ecosystems (e.g., home, school, community, host culture) that contribute to one’s ethnic identity formation and/or sexual identity development; gain insight about theories and models of identity development and associated attitudes, beliefs, values, and acculturative experiences.

Recognize unique and universal characteristics affiliated with various cultural, ethnic, and racial communities attending our counselling settings.

Identify how power, privilege, prejudice, racism, and oppressive systems impact multicultural/immigrant/BIPOC clients, as they relate to different social identities and to the practice of counselling.

Become further aware of the barriers encountered by BIPOC in accessing or seeking mental health support.

Unlearn and relearn strategies relevant in our work with multicultural communities; this may include, but is not limited to:

Challenging one’s implicit biases and internalized values

Testing assumptions and generalized stereotypes

Reflecting upon one’s safe and effective use of self

Embodying cultural humility and social justice causes

Utilizing Eastern and decolonized ideologies

Integrating trauma-informed, antiracist, and anti-oppressive practices

Applying culturally responsive/affirming techniques within a safe counselling space.

These intentions were accompanied by course assignments that encouraged students to effectively apply theory into practice by means of creating a cultural genogram and autobiography, designing a culturally responsive treatment plan, as well as punctuating the course with the submission of a self-reflective journal.

8. What self-care strategies do you use to maintain your well-being while supporting clients who may be experiencing similar stressors?

To complement this work, I engage in daily self-care practices. Depending on my capacity, this might look like:

Practicing various forms of self-care:

Emotional (journaling, therapy, meditation)

Physical (walking, resting)

Spiritual (praying, yoga)

Intellectual (reading, puzzling, learning a new language)

Practical (trying new recipes, decluttering)

… anything that is going to help reduce stress and keep you grounded

As a practitioner, I also:

Participate in individual clinical supervision

Debrief with colleagues after challenging client sessions

Develop a consistent sleep hygiene routine

Stay hydrated

Incorporate movement and be properly nourished

Engage in personal therapy to discuss potential vicarious trauma (in and out of the therapeutic space).

9. Looking back on your journey, what are you most proud of?

This is a great question! I think the aspect of my journey I am most proud of is researching topics about cultural preservation, identity formation, trauma, and systemic oppression that lend themselves well to facilitating educational, informative, and meaningful conversations with my partner and daughters. I am proud that my daughters have embodied tremendous self-awareness, developed a secure bicultural identity, understand the importance of advocating for social justice causes and being a productive ally. As I mentioned in my book, intergenerational dialogue about these timely topics truly starts in the home milieu, where words can be put to action.